This is a penultimate “breather” post, insofar as it doesn’t present much new material, but summarizes much of what’s in the previous 20 essays. It’s now time to tie everything together and Solve It. This series has reached enough bulk that such an endeavor requires two posts: one to tie it all together (Part 21) and one to discuss solutions (Part 22). Let me try to put the highlights from everything I’ve covered into a coherent whole. That may prove hard to do; I might not succeed. But I will try.

This will be long and repeat a lot of previous material. There are two reasons for that. First, I intend this essay to be a summarization of some highlights from where we’ve been. Second, I want it to stand alone as a “survey course” of the previous 20 essays, so that people can understand the highlights (and, thus, understand what I propose in the conclusion) even if they haven’t read all the prior material.

If I were to restart this series of posts (for which I did not intend it, originally, to reach 22 essays and 92+ kilowords) I would rename it Why Does Work Suck? In fact, if I turn this stuff into a book, that’s probably what I’ll name it. I never allowed myself to answer, “because it’s work, duh.” We’re biologically programmed to enjoy working. In fact, most of the things people do in their free time (growing produce, unpaid writing, open-source programming) involve more actual work than their paid jobs. Work is a human need.

How Does Work Suck?

There are a few problems with Work that make it almost unbearable, driving it into such a negative state that people only do it for the lack of other options.

- Work Sucks because it is inefficient. This is what makes investors and bosses angry. Getting returns on capital either requires managing it, which is time-consuming, or hiring a manager, which means one has to put a lot of trust in this person. Work is also inefficient for average employees (MacLeod Losers) which is why wages age so low.

- Work Sucks because bad people end up in charge. Whether most of them are legitimately morally bad is open to debate, but they’re certainly a ruthless and improperly balanced set of people (MacLeod Sociopath) who can be trusted to enforce corporate statism. Over time, this produces a leadership caste that is great at maintaining power internally but incapable of driving the company to external success.

- Work Sucks because of a lack of trust. That’s true on all sides. People are spending 8+ hours per day on high-stakes social gambling while surrounded by people they distrust, and who distrust them back.

- Work Sucks because so much of what’s to be done in unrewarding and pointless. People are glad to do work that’s interesting to them or advances their knowledge, or work that’s essential to the business because of career benefits, but there’s a lot of Fourth Quadrant work for which neither applies. This nonsensical junk work is generated by strategically blind (MacLeod Clueless) middle managers and executed by rationally disengaged peons (MacLeod Losers) who find it easier to subordinate than to question the obviously bad planning and direction.

All of these, in truth, are the same problem. The lack of trust creates the inefficiencies that require moral flexibility (convex deception) for a person to overcome. In a trust-sparse environment, the people who gain people are the least deserving of trust: the most successful liars. It’s also the lack of trust that generates the unrewarding work. Employees are subjected, in most companies, to a years-long dues-paying period which is mostly evaluative– to see how each handles unpleasant make-work and pick out the “team players”. The “job” exists to give the employer an out-of-the-money call option on legitimately important work, should it need some done. It’s a devastatingly bad system, so why does it hold up? Because, for two hundred years, it actually worked quite well. Explaining that requires delving into mathematics, so here we go.

Love the Logistic

The most important concept here is the S-shaped logistic function, which looks like this (courtesy of Wolfram Alpha):

![]()

The general form of such a function L(x; A, B, C) is:

![]()

where A represents the upper asymptote (“maximum potential”), B represents the rapidity of the change, and C is a horizontal offset (“difficulty”) representing the x-coordinate of the inflection point. The graph above is for L(x; 1, 1, 0).

Logistic functions are how economists generally model input-output relationships, such as the relationship between wages and productivity. They’re surprisingly useful because they can capture a wide variety of mathematical phenomena, such as:

- Linear relationships; as B -> 0, the relationship becomes locally linear around the inflection point, (C, A/2).

- Discrete 0/1 relationships: as B -> infinity, the function approaches a “step function” whose value is A for x > C and 0 for x < C.

- Exponential (accelerating) growth: If B > 0, L(x; A, B, C) is very close to being exponential at the far left (x << C). (Convexity.)

- Saturation: If B > 0, L(x; A, B, C) is approaching A with exponential decay at the far right (x >> C). (Concavity.)

Let’s keep inputs abstract but assume that we’re interested in some combination of skill, talent, effort, morale and knowledge called x with mean 0 and “typical values” between -1.0 and 1.0, meaning that we’re not especially interested in x = 10 because we don’t know how to get there. If C is large (e.g. C = 6) then we have an exponential function for all the values we care about: convexity over the entire window. Likewise, leftward C values (e.g. C = -6) give us concavity over the whole window.

Industrial work, over the past 200 years, has tended toward commoditization, meaning that (a) a yes/no quality standard exists, increasing B, and (b) it’s relatively easy for most properly set-up producers to meet it most of the time (with occasional error). The result is a curve that looks like this one, L(x; 10, 4.5, -0.7), which I’ll call a(x):

![]()

Variation, here, is mainly in incompetence. Another way to look at it is in terms of error rate. The excellent workers make almost no errors, the average ones achieve 95.8% of what is possible (or a 4.2% error rate) with the mediocre (x = -0.5) making almost 5 times as many mistakes (28.9% error rate), and the abysmal unemployable with an error rate well over 50%. This is what employment has looked like for the past two hundred years. Why? Because an industrial process is better modeled as a complex network of these functions, with outputs from one being inputs to another. The relationship of individual wage into morale, morale into performance, performance into productivity, and individual productivity into firm productivity, and firm productivity into profitability, can all be modeled as S-shaped curves. With this convoluted network of “hidden nodes” that exists in a context of a sophisticated industrial operation, it’s generally held to be better to have a consistently high-performing (B high, C negative) node than higher-performing but variable node.

One way to understand the B in the above equation is that it represents how reliably the same result is achieved, noting the convergence to a step function as B goes to infinity. In this light, we can understand mechanization. Middle grades of work rarely exist with machines. In the ideal, they either execute perfectly, or fail perfectly (and visibly, so one can repair them). Further refinements to this process are seen in the changeover from purely mechanical systems to electronic ones. It’s not always this way, even with software. There are nondeterministic computer behaviors that can produce intermittent bugs, but they’re rare and far from the ideal.

As I’ve discussed, if we can define perfect performance (i.e. we know what A, the error-free yield, looks like) then we can program a machine to achieve it. Concave work is being handed over to machines, with the convex tasks remaining available. With convexity, it’s rare that one knows what A and B are. On explored values, the graph just looks like this one, for L(x; 200, 2.0, 1.5), which I’ll call b(x):

![]()

It shows no signs of leveling off and, for all intents and purposes, it’s exponential. This is usually observed for creative work where a few major players (the “stars”) get outsized rewards in comparison to the average people.

Convexity Isn’t Fair

Let’s say that you have two employees, one of whom (Alice) is slightly above average (x = 0.1) and the other of whom (Bob) is just average (x = 0.0). You have the resources to provide 1.0 full point of training, and you can split it anyway you choose (e.g. 0.35 points for Alice, and 0.65 points for Bob). Now, let’s say that you’re managing concave work modeled by the function L(x; 100, 2.0, -0.3), which is concave.

Let the x-axis represent the amount of training (0.0 to 1.0) given to Alice, with the remainder given to Bob. Here’s a graph of their individual productivity levels, with Alice in blue, Bob in purple, and their sum productivity in the green curve

![]()

If we zoom in to look at the sum curve, we see a maximum at x = 0.45, an interior solution where both get some training.

![]()

At x = 0.0 (full investment in Bob) Alice is producing 69.0 points and Bob’s producing 93.1, for a total of 162.1.

At x = 0.5 (even split of training) Alice in producing 85.8 points and Bob’s producing 83.2, for a total of 169.0.

At x = 1.0 (full investment in Alice) Alice is producing 94.3 points and Bob’s producing 64.6, for a total of 158.9.

The maximal point is x = 0.45, which means that Alice gets slightly less training because Bob is further behind and needs it more. Both end up producing 84.55 points, for a total of 169.1. After the training is disbursed, they’re at the same level of competence (0.55). This is a “share the wealth“ interior optimum that justifies sharing the training.

Let’s change to a convex world, with the function L(x; 320, 2.0, 1.1). Then, for the same problem, we get this graph (blue representing Alice’s productivity, purple representing Bob’s, and the green curve representing the sum):

Zooming in on the graph sum productivity, we find that the “fair” solution (x = 0.45) is the worst!

![]()

At x = 0.0 (full investment in Bob) Alice is producing 38.1 points and Bob’s producing 144.1, for a total of 182.2.

At x = 0.5 (even split of training) Alice in producing 86.1 points and Bob’s producing 74.1, for a total of 160.2.

At x = 1.0 (full investment in Alice) Alice is producing 160.0 points and Bob’s producing 31.9, for a total of 191.9.

The maxima are at the edges. The best strategy is to give Alice all of the training, but giving all to Bob is better than splitting it evenly, which is about the worst of the options. This is a “starve the poor” optimum. It favors picking a winner and putting all the investment into one party. This is how celebrity economies work. Slight differences in ability lead to massive differences in investment and, ultimately, create a permanent class of winners. Here, choosing a winner is often more important than getting “the right one” with the most potential.

Convexity pertains to decisions that don’t admit interior maxima, or for which such solutions don’t exist or make sense. For example, choosing a business model for a new company is convex, because putting resources into multiple models would result in mediocre performance in all of them, thus failure. The rarity of “co-CEOs” seems to indicate that choosing a leader is also a convex matter.

Convexity is hard to manage

In optimization, convex problems tend to be the easier ones, so the nomenclature here might be strange. In fact, this variety of convexity is the exact opposite of convexity in labor. Optimization problems are usually framed in terms of minimization of some undesirable quantity like cost, financial risk, statistical error, or defect rate. Zero is the (usually unattainable) perfect state. In business, that would correspond to the assumption that an industrial apparatus has an idealized business model and process, with the management’s goal to drive execution error to zero.

What makes convex minimization methods easier is that, even in a high-dimensional landscape, one can converge to the optimal point (global minimum) by starting from anywhere and iteratively stepping in the direction recommended by local features (usually, first and second derivative). It’s like finding the bottom point in a bowl. Non-convex optimizations are a lot harder because (a) there can be multiple local optima, which means that starting points matter, and (b) the local optima might be at the edges, which has its own undesirable properties (including, with people, unfairness). The amount of work required to find the best solutions is exponential in the number of dimensions. That’s why, for example, computers can’t algorithmically find the best business model for a “startup generator”. Even if it were a well-formed problem, the dimensionality would be high and the search problem intractable (probably).

Convex labor is analogous to non-convex optimization problems while management of concave labor is analogous to convex optimization. Sorry if this is confusing. There’s an important semantic difference to highlight here, though. With concave labor, there is some definition of perfect completion so that error (departure from that) can be defined and minimized with a known lower bound: 0. With convex labor, no one knows what the maximum value is, because the territory is unexplored and the “leveling off” of the logistic curve hasn’t been found yet. It’s natural, then, to frame that as a maximization problem without a known bound. With convex labor, you don’t know what the “zero-or-max” point is because no one knows how well one can perform.

Concave labor is the easy, nice case from a managerial perspective. While management doesn’t literally implement gradient descent, it tends to be able to self-correct when individual labor is concave (i.e. the optimization problem is convex). If Alice starts to pull ahead while Bob struggles, management will offer more training to Bob.

However, in the convex world, initial conditions matter. Consider the Alice-Bob problem above with the convex productivity curve, and the fact that splitting the training equitably is the worst possible solution. Management would ideally recognize Alice’s slight superiority and give her all the training, thus finding the optimal “edge case”. But what if Bob managed (convex dishonesty) to convince management that he was slightly superior to Alice and at, say, x = 0.2? Then Bob would get all the training, and Alice would get none, and management would converge on a sub-optimal local maximum. That is the essence of corporate backstabbing, is it not? Management’s increasing awareness of convexity in intellectual work means that it will tend to double down its investment in winners and toss away (fire) the losers. Thus, subordinates put considerable effort into creating the appearance of high potential for the sake of driving management to a local maximum that, if not necessarily ideal for the company, benefits them. That’s what “multiple local optima” means, in practical terms.

The traditional three-tiered corporation has a firm distinction between executives and managers (the third tier being “workers”, who are treated as a landscape feature) and its pertains to this. Because business problems are never entirely concave and orderly, the local “hill climbing” is left to managers, while the convex problems (which, like choosing initial conditions, require non-local insight) such as selecting leaders and business models are left to executives.

Yet with everything concave being performed, or soon to be performed, by machines, we’re seeing convexity pop up everywhere. The question of which programming languages to learn is a convex decision that non-managerial software engineers have to make in their careers. Picking a specialty is likewise; convexity is why it’s of value to specialize. The most talented people today are becoming self-executive, which means that they take responsibility for non-local matters that would otherwise be left to executives, including the direction of their own career. This, however, leads to conflicts with authority.

Older managers often complain about Millennial self-executivity and call it an attitude of entitlement. Actually, it’s the opposite. It’s disentitlement. When you’re entitled, you assume social contracts with other people and become angry when (from your perception) they don’t hold up their end. Millennials leave jobs, and furtively use slow periods to invest in their careers (e.g. in MOOCs) rather than asking for more work. That’s not an act of aggression or disillusion; it’s because they don’t believe the social contract ever existed. It’s not that they’re going to whine about a boss who doesn’t invest in their career– that would be entitlement– because that would do no good. They just leave. They weren’t owed anything, and they don’t owe anything. That’s disentitlement.

Convexity is bad for your job security

Here’s some scary news. When it comes to convex labor, most people shouldn’t be employed. First, let me show a concave input-output graph for worker productivity, assuming even distribution in worker ability from -1.0 to 1.0. Our model also assumes this ability statistic to be inflexible; there’s no training effect.

![]()

The blue line, at 82.44, represents the mean worker in the population. Why’s this important? It represents the expected productivity of a new hire off the street. If you’re at the median (x = 0.0) or even a bit below it, you are “above average”. It’s better to retain you than to bring someone in off the street. Let’s say that John is 40th percentile (x = -0.2) hire, which means that his productivity is 90. A random person hired off the street will be better than John, 60% of the time. However, the upside is limited (10 points at most) and the downside (possibly 70 points) is immense so, on average, it’s a terrible trade. It’s better to keep John (a known mediocre worker) on board than to replace him.

With a convex example, we find the opposite to be true:

![]()

Here, we have an arrangement in which most people are below the mean, so we’d expect high turnover. Management, one expects, would be inclined to hire people on a “try out” basis with the intention of throwing most of them back on the street. An average or even good (x = 0.5) hire should be thrown out in order to “roll the dice” with a new hire who might be the next star. Is that how managers actually behave? No, because there are frictional and morale reasons not to fire 80% of your people, and because this model’s assumption that people are inflexibly set at a competence level is not entirely true for most jobs, and those where it is true (e.g. fashion modeling) make it easy for management to evaluate someone before a hire is made. In-house experience matters. That is, however, how venture capital, publishing and record labels work. Once you turn out a couple failures, with those being the norm, it might still be that you’re a high performer who’s been unlucky, but you’re judged inferior to a random new entrant (with more upside potential) and flushed out of the system.

In the real world, it’s not so severe. We don’t see 80% of people being fired, and the reason is that, for most jobs, learning matters. The above applies to work at which there’s no learning process, but each worker is inflexibly put at a certain perfectly measurable productivity level. That’s not how the world really works. In-born talent is one relevant input, but there are others like skill, in-house experience, and education that have defensive properties and keep a person’s job security. People can often get themselves above the mean with hard work.

Secondly, the model above assumes workers are paid equally, which is not the case for most convex work. In the convex model above, the star (x = 1.0) might command several times the salary of the average performer (x = 0.0) and he should. That compensation inequality actually creates job security for the rest of them. If the best people didn’t charge more for their work, then employers would be inclined to fire middling performers in the search of a bargain.

This may be one of the reasons why there is such high turnover in the software industry. You can’t a get seasoned options trader for under $250,000 per year, but you can get excellent programmers (who are worth 5-10 times that amount, if given the right kind of work) for less than half of that. This is often individually justified (by the engineer) with an attitude of, “well, I don’t need to be paid millions; I care more about interesting work”. As an individual behavior, that’s fine, but it might be why so many software employers are so quick to toss engineers aside for dubious reasons. Once the manager concludes that the individual doesn’t have “star” potential, it’s worth it to throw out even a good engineer and try again for a shot at a bargain, considering the number of great engineers at mediocre salary levels.

One thing I’ve noticed in software (which is highly convex) is that there’s a cavalier attitude toward firing, and it’s almost certainly related to that “star economy” effect. What’s different is that software convexity has a lot inputs other that personal ability– project/person fit, tool familiarity, team cohesion, and a lot factors that are so hard to detect that they feel like pure luck– in the mix, so the “toss aside all but the best” strategy is severely defective, at least for a larger organization that should be enabling people to find better fitting projects, which makes a lot of sense amid convexity. That’s one of the reasons why I am so dogmatic about open allocation, at least in big companies.

Convexity is risky

Job insecurity amid convexity is an obvious problem, but not damning. If there’s a fixed demand for widgets, a competitor who can produce 10 times more of them is terrifying, because it will crash prices and put everyone else out of business (and, then, become a monopolist and raise them). Call that “red ocean convexity”, where the winners put the losers out of business because a “10X” performer takes 9X from someone else. However, if demand is limitless, then the presence of superior players isn’t always a bad thing. A movie star making $3 million isn’t ruined by one making $40 million. The arts are an example of “blue ocean convexity”, insofar as successful artists don’t make the others poorer, but increase the aggregate demand of art. It’s not “winner-take-all” insofar as one doesn’t have to be the top player to add something people value.

Computational problem solving (not “programming”) is a field where there’s very high demand, so the fact that top performers will produce an order of magnitude more value (the “10X effect”) doesn’t put the rest out of business. That’s a very good thing, because most of those top performers were among “the rest” when they started their career. Not only is there little direct competition, but as software engineers, we tend to admire those “10X” people and take every opportunity we can get to learn from them. If there were more of them, it wouldn’t make us poorer. It would make the world richer.

Is demand for anything limitless, though? For industrial products, no. Demand for televisions, for example, is limited by peoples’ need for them and space to put them. For making peoples’ lives better, yes. For improving processes, sure. Generation of true wealth (as Paul Graham defines it: “stuff people want”) is something for which there’s infinite demand, at least as far as we can see. So what’s the limiting factor? Why can’t everyone work on blue-ocean convex work that makes peoples’ lives better? It comes down to risk. So, let’s look at that. The model I’m going to use is as follows:

- We only care about the immediate neighborhood of a specific (“typical”) competence level. We’ll call it x = 0.

- Tasks have a difficulty t between -1.0 and 2.0, which represents the C in the logistic form. B is going to be a constant 4.5; just ignore that.

- The harder a task is, the higher the potential payoff. Thus, I’ll set A = 100 * (1 + e^(5*t)). This means that work gets more valuable slightly faster (11% faster) than it gets harder (“risk premium”). The constant term in A is based on the understanding that even very easy (difficulty of -1.0) work has value insofar as it’s time-consuming and therefore people must be paid to do it.

- We measure risk for a given difficulty t by taking the first derivative of L(x; …), with respect to x, at x = 0. Why? L’(x; …) tells us how sensitive the output (payoff) is to marginal changes in input. We’re modeling unknown input variables and plain luck factors as a random, zero-mean “noise” variable d and assuming that for known competence x the true performance will be L(x + d; …). So this first derivative tells us, at x = 0, how sensitive we are to that unknown noise factor.

What we want to do is assess the yield (expected value) and risk (first derivative of yield) for difficulty levels from -1 to 2 when known x = 0. Here’s a graph of expected yield:

![]()

It’s hard to notice on that graph, but there’s actually a slight “dip” or “uncanny valley” as one goes from the extreme of easiness (t = -1.0) to slightly harder (-1.0 < t < 0.0) work:

![]()

Does it actually work that way in the real world? I have no idea. What causes this in the model is that, as we go from the ridiculously easy (t = 1.0) to the merely moderately easy (t = 0.5) the rate of potential failure grows faster than the maximum potential A does, as a function of t. That’s an artifact of how I modeled this and I don’t know for sure that a real-world market would have this trait. Actually, I doubt it would. It’s a small dip so I’m not going to worry about it. What we do see is that our yield is approximately constant as a function of difficulty for t from -1.0 to 0.0, where the work is concave for that level of skill; and then it grows exponentially as a function of t from 0.0 to 2.0, where the work is convex. That is what we tend to see on markets. The maximal market value of work (1 + e^(5 * t) in this model) grows slightly faster than difficulty in completing it (1 + e^(4.5*t), here).

However, what we’re interested in is risk, so let me show that as well by graphing the first derivative of L with respect to x (not t!) for each t.

![]()

What this shows us, pretty clearly, is monotonic risk increase as the tasks become more difficult. That’s probably not too surprising, but it’s nice to see what it looks like on paper. Notice that the easy work has almost no risk involved. Let’s plot these together. I’ve taken the liberty of normalizing the risk formula (in purple) to plot them together, which is reasonable because our units are abstract:

![]()

Let’s look at one other statistic, which will be the ratio between yield and risk. In finance, this is called the Sharpe Ratio. Because the units are abstract (i.e. there’s no real meaning to “1 unit” of competence or difficulty) there is no intrinsic meaning to its scale, and therefore I’ve again taken the liberty of normalizing this as well. That ratio, as a function of task difficulty, looks like this…

![]()

…which looks exactly like affine exponential decay. In fact, that’s what it is. The Sharpe Ratio is exponentially favorable for easy work (t < 0.0) and approaches a constant value (1.0 here, because of the normalization) for large t.

What’s the meaning of all this? Well, traditionally, the industrial problem was to maximize yield on capital within a finite “risk budget”. If that’s the case– you’re constrained by some finite amount of risk– then you want to select work according to the Sharpe Ratio. Concave tasks might have less yield, but they’re so low in risk that you can do more of them. For each quantum of risk in your budget, you want to get the most yield (expected value) out of it that you can. This favors the extreme concave labor. This is why industrial labor, for the past 200 years, has been almost all concave. Boring. Reliable. In many ways, the world still is concave and that’s a desirable thing. Good enough is good enough. However, it just so happens that when we, as humans, master a concave task when tend to look for the convex challenge of making it run itself. In pre-technological times, this was done by giving instructions to other people, and making machines as easy as possible for humans to use. In the technological era, it’s done with computers and code. Even the grunt work of coding is given to programs (we call them compilers) so we can focus on the interesting stuff. We’re programming all of that concave work out of human hands. Yes, concave work is still the backbone of the industrial world and always will be. It’s just not going to require humans doing it.

What if, instead, the risk budget weren’t an issue? Let’s say that we have a team of 5 programmers given a year to do whatever they want, and the worst they can do is waste their time, and you’re okay with that maximal-risk outcome (5 annual salaries for a learning experience). They might build something amazing that sells for $100 million, or they might work for a year and have the project still fail on the market. Maybe they do great work, but no one wants it; that’s a risk of creation. In this case, we’re not constrained by risk allocation but by talent. We’ve already accepted the worst possible outcome as acceptable. We want them to be doing convex work, which has the highest yield. Those top-notch people are the limiting resource, not risk allocation.

Convexity requires teamwork

Above, I established that if individual productivity is a convex function of investment in that person, and group performance is a sum of individual productivity, then the optimal solution is to ply one person with resources and starve (and likely fire) the rest. Is that how things actually work? No, not usually. There’s a glaring false assumption, which is the additive model where group performance is a simple sum of individual performances. Real team efforts shouldn’t work that way.

When a team is properly configured, most of their efforts don’t merely add to some pile of assets, but they multiply each others’ productivity. Each works to make the others more successful. I wrote about this advancement of technical maturity (from multiplier to adder) as it pertains to software but I think it’s more general. Warning: incompetent attempts at multiplier efforts are every bit as toxic as incompetent management and will have a divider effect.

Team convexity is a bit unique in the sense that both sides of the logistic “S-curve” are observed. You have synergy (convexity) as the team scales up to a certain size, but congestion (concavity) beyond a certain point. It’s very hard to get team size and configuration right, and typical “Theory Z” management (which attempts to coerce a heterogeneous set of people who didn’t choose each other, and probably didn’t choose the project, into being a team) generally fails at this. It can’t be managed competently from a top-down perspective, despite what many executives say (they are wrong). It has to be grass-roots self-organization. Top-down, closed-allocation management can work well in the Alice/Bob models above where productivity is the sum of individual performances (i.e. team synergies aren’t important) but it fails catastrophically on projects that require interactive, multiplicative effects in order to be successful.

Convexity has different rules

The technological economy is going to be very different, because of the way business problems are formulated. In the industrial economy, capital was held in some fixed amount by a business, whose goal was to gain as much yield (profit or interest) from it while keeping risk within certain bounds deemed acceptable. That made concavity desirable. It still is; stable income with low variation is always a good thing. It’s just that such work no longer requires humans. Concave work has been so commoditized that it’s hard to get a passive profit from it.

Ultimately, I think a basic income is the only way society will be able to handle widespread convexity of individual labor. What does it say about the future? People will either be very highly compensated, or effectively unemployed. There will be an increasing need for unpaid learning while people push themselves from the low, flat region of a convex curve to the high, steep part. Right now, we have a society where people with the means to indulge in that can put themselves on a strong career track, but the majority who have a lifelong need for monthly income end up getting shafted: they become a permanent class of unskilled labor and, by keeping wages low, they actually hold back technological advancement.

Industrial management was risk-reductive. A manager took ownership of some process and his job was to look for ways it could fail, then tried to reduce the sources of error in that process. The rare convex task (choosing a business strategy) was for a higher order of being, an executive. Technological management has to embrace risk, because all the concave work’s being taken by machines. In the future, it will only be economical for a human to do something when perfect completion is unknown or undefinable, and that’s the convex work.

A couple more graphs deserve attention, because both pertain to managerial goals. There are two ways that a manager can create a profit. One is to improve output. The other is to reduce costs. Which is favorable? It depends. Below is a graph that shows productivity ($/hour) as a function of wages for some task where performance is assumed to be convex in wages. The relationship is assumed here to be inflexible and go both ways: better people will expect more in wages, low wages will cause peoples’ out-of-work distractions to degrade their performance. Plotted in purple is the y = x or “break-even” line.

![]()

As one can see, it doesn’t even make sense to hire people for this kind of work at less than $68/hour: they’ll produce less than they cost. That “dip” is an inherent problem for convex work. Who’s going to pay people in the $50/hour range so they can become good and eventually move to the $100/hour range (where they’re producing $200/hour work)? This naturally tends toward a “winners and losers” scenario. The people who can quickly get themselves to the $70/hour productivity level (through the unpaid acquisition of skill) are employable, and will continue to grow; the rest will not be able to justify wages that sustain them. The short version: it’s hard to get into convex work.

Here’s a similar graph for concave work:

![]()

… and here’s a graph of the difference between productivity and wage, or per-hour profit, on each worker:

![]()

So the optimal profit is achieved at $24.45 per hour, where the worker provides $56.33 worth of work in that time. It doesn’t seem fair, but improvements to wages beyond that, while they improve productivity, do not improve it by enough to justify the additional cost. That’s not to say that companies will necessarily set wages to that level. (They might raise them higher to attract more workers, increasing total profit.) Also, here is a case where labor unions can be powerful (they aren’t especially helpful with convex work): in the above, the company would still earn a respectable profit on each worker with wages as high as $55 per hour, and wouldn’t be put out of business (despite managements’ claim that “you’ll break us” at, say, $40) until almost $80.

The tendency of corporate management toward cost-cutting, “always say no”, and Theory-X practices is an artifact of the above result of concavity. So while I can argue that “convexity is unfair” insofar as it encourages inequality of investment and resources, enabling small differences in initial conditions to produce a winner-take-all outcome; concavity produces its own variety of unfairness, since it often encourages wages to go to a very low level, where employers take a massive surplus.

The most important problem…?

Above is a lot about convexity, but I feel like the changeover to convexity in individual labor is the most important economic issue of the 21st century. So if we want to understand why the contemporary, MacLeod-hierarchical, organization won’t survive it, we need a deep understanding of what convexity is and how it works. I think we have that, now.

What does this have to do with Work Sucking? Well, there are a few things we get out of it. First, for the concave work that most of the labor force is still doing…

- Concave (“commodity”) labor leads to grossly unfair wages. This creates a natural adversity between workers and management on the issue of wage levels.

- Management has a natural desire to reduce risk and cut costs, on an assumption of concavity. It’s what they’ve been doing for over 200 years. When you manage concave work, that’s the most profitable thing to do.

- Management will often take a convex endeavor (e.g. computer programming) and try to treat it as concave. That’s what we, in software, call the “commodity developer” culture that clueless software managers try to shove down hapless engineers’ throats.

- Stable, concave work is disappearing. Machines are taking it over. This isn’t a bad thing (on the contrary, it’s quite good) but it is eroding the semi-skilled labor base that gave the developed world a large middle class.

Now, for the convex:

- Convex work favors low employment and volatile compensation. It’s not true that there “isn’t a lot of convex work” to go around. In fact, there’s a limitless amount of demand for it. However, one has to be unusually good for a company to justify paying for it at a level one could live on, because of the risk. Without a basic income in place, convexity will generate an economy where income volatility is at a level beyond what people are able to accept. As a firm believer in the need for market economies, this must be addressed.

- Convex payoffs produce multiple optima on personnel matters (e.g. training, leadership). This sounds harmless until one realizes that “multiple optima” is a euphemism for “office politics”. It means there isn’t a clear meritocracy, as performance is highly context-sensitive.

- Convex work often creates a tension between individual competition and teamwork. Managers attempting to grade individuals in isolation will create a competitive focus on individual productivity, because convexity rewards acceleration of small individual differences. This managerial style works for simple additive convexity, but fails in an organization that needs people to have multiplicative or synergistic effects (team convexity) and that’s most of them.

Red and blue ocean convexity

One of the surprising traits of convexity, tied-in with the matter of teamwork, is that it’s hard to predict whether it will be structurally cooperative or competitive. This leads me to believe that there are fundamental differences between “red ocean” and “blue ocean” varieties of convexity. For those unfamiliar with the terms, red ocean refers to well-established territory in which competition is fierce. There’s a known high quantity of resources (“blood in the water”) available but there’s a frenzy of people (some with considerable competitive advantages) working to get at it. It’s fierce and if you aren’t strong, the better predators will crowd you out. Blue ocean refers to unexplored territory where the yields are unknown but the competition’s less fierce (for now).

I don’t know this industry well, but I would think that modeling is an example of red-ocean convexity. Small differences in input (physical attractiveness, and skill at self-marketing) result in massive discrepancies of output, but there’s a small and limited amount of demand for the work. If there’s a new “10X model” on the scene, all the other models are worse off, because the supermodel takes up all of the work. For example, I know that some ridiculous percentage of the world’s hand-modeling is performed by one woman (who cannot live a normal life, due to her need to protect her hands).

What about professional sports, the distilled essence of competition? Blue ocean. Yep. That might seem surprising, given that these people often seem to want to kill each other, but the economic goal of a sports team is not to win games, but to play great games that people will pay money to watch. A “10X” player might revitalize the reputation of the sport, as Tiger Woods did for golf, and expand the audience. Top players actually make a lot of money for the opponents they defeat; the stars get a larger share of the pool, meaning their opponents get a smaller percentage, but they also expand that pool so much that everyone gets richer.

How about the VC-funded startup ecosystem? That’s less clear. Business formation is blue ocean convexity, insofar as there are plenty of untapped opportunities to add immense value, and they exist all over the world. However, fund-raising (at least, in the current investor climate) and press-whoring are red ocean convexity: a few already-established (and complacent) players get the lion’s share of the attention and resources, giving them an enormous head start. Indeed, this is the point of venture capital in the consumer-web space: use the “rocket fuel” (capital infusion) to take a first-entrant advantage before anyone else has a shot.

Red and blue ocean convexity are dramatically different in how they encourage people to think. With red-ocean convexity, it’s truly a ruthless, winner-take-all, space because the superior, 10X, player will force the others out of business. You must either beat him or join him. I recommend “join”. With blue-ocean convexity (which is the force that drives economic growth) outsized success doesn’t come at the expense of other people. In fact, the relationship may be symbiotic and cooperative. For example, great programmers build tools that are used all over the world and make everyone better at their jobs. So while there is a lot of inequality in payoffs– Linus Torvalds makes millions per year, I use his tools– because that’s how convexity works, it’s not necessarily a bad thing because everyone can win.

Convexity and progress

Convexity’s most important property is progressive time. Real-world convexity curves are often steeper than the ones graphed above and, if there isn’t a role for learning, then the vast majority of people will be unable to achieve at a level supporting an income, and thus unemployed. For example, while practice is key in (highly convex) professional sports, there aren’t many people who have the natural talent to earn a living at it. Convexity shuts out those without natural talent. Luckily for us and the world, most convex work isn’t so heavily influenced by natural limitations, but by skills, specialization and education. There’s still an elite at the rightward side of the payoff distribution curve that takes the bulk of the reward, but it’s possible for a diligent and motivated person to enter that elite by gaining the requisite skills. In other words, most of the inputs into that convex payoff function are within the individual actor’s control. This is another case of “good inequality”. In blue-ocean convexity, we want the top players to reap very large rewards, because it motivates more people to do the work that gets them there.

Consider software engineering, which is perhaps the platonic ideal of blue-ocean convexity. What retards us the most as an industry is the lack of highly-skilled people. As an industry, we contend with managerial environments tailored to mediocrity, and suffer from code-quality problems that can reduce a technical asset’s real value to 80, 20, or even minus-300 cents on the dollar compared to its book value. Good software engineers are rare, and that hurts everyone. In fact, perhaps the easiest way to add $1 trillion in value to the economy would be to increase software engineer autonomy. Because most software engineers never get the environment of autonomy that would enable them to get any good, the whole economy suffers. What’s the antidote? A lot of training and effort– the so-called “10000 hours” of deliberate practice– that’s generally unpaid in this era of short-term, disposable jobs.

Convexity’s fundamental problem is that it requires highly-skilled labor, but no employer is willing to pay for people to develop the relevant skills, out of a fear that employees who drive up their market value will leave. In the short term, it’s an effective business strategy to hire mediocre “commodity developers” and staff them on gigantic teams for uninspiring projects, and give them work that requires minimal intellectual ability aside from following orders. In the long term, those developers never improve and produce garbage software that no one knows how to maintain, producing creeping morale decay and, sometimes, “time bombs” that cause huge business losses at unknown times in the future.

That’s why convexity is such a major threat to the full-employment society to which even liberal Americans still cling. Firms almost never invest in their people– empirically, we see that– in favor of the short-term “solution”, which is to ignore convexity and try to beat the labor context into concavity, that is terrible in the long term. Thus, even in convex work, the bulk of people linger at the low-yield leftward end of the curve. Their employers don’t invest in them, and often they lack the time and resources to invest in themselves. What we have, instead of blue-ocean convexity, is an economy where the privileged (who can afford unpaid time for learning) become superior because they have the capital to invest in themselves, and the rest are ignored and fall into low-yield commodity work. This was socially stable when there was a lot of concave, commodity work for humans to do, but that’s increasingly not the case.

Someone is going to have to invest in the long term, and to pay for progress and training. Right now, privileged individuals do it for themselves and their progeny, but that’s not scalable and will not avert the social instability threatened by systemic, long-term unemployment.

Trust and convexity

As I’ve said, convexity isn’t only a property of the relationship between individual inputs (talent, motivation, effort, skill) and productivity, but also occurs in team endeavors. Teams can be synergistic, with peoples’ efforts interacting multiplicatively instead of additively. That’s a very good thing, when it happens.

So it’s no surprise that large accomplishments often require multiple people. We already knew that! That is less true in 2013 than it was 1985– now, a single person can build a website serving millions– but it’s still the case. Arguably, it’s more the case now; it’s only that many markets have become so efficient that interpersonal dependencies “just work” and give more leverage to single actors. (The web entrepreneur is using technologies and infrastructure built by millions of other people.) At any rate, it’s only a small space of important projects that will be accomplished well by a single party, acting alone. For most, there’s a need to bring multiple people together, but to retain focus and that requires interior political inequalities (leadership) to the group.

We’re hard-wired to understand this. As humans, we fundamentally get the need for team endeavors with strong leadership. That’s why we enjoy team sports so much.

Historically, there have been three “sources of power” that have enabled people to undertake and lead large projects (team convexity):

- coercion, which exists when negative consequences are used to motivate someone to do work that she wouldn’t otherwise do. This was the cornerstone of pre-industrial economies (slavery) but is also used, in a softer form, by ineffective managers: do this or lose your income/reputation. Anyway, coercion is how the Egyptian pyramids were built: coercive slave labor.

- divination, in which leaders are elected based on an abstract principle, which may be the whim of a god, legal precedent, or pure random luck. For example, it has been argued that gambling (a case of “pure random luck”) served a socially positive purpose on the American frontier. Although it moved funds “randomly”, it allowed pools of capital to form, financing infrastructural ventures. Something like divination is how the cathedrals were built: voluntary labor, motivated by religious belief, directed by architects who often were connected with the Church. Self-divination, which tends to occur in a pure power vacuum, is called arrogation.

- aggregation, where an attempt to compute, fairly, the group preference or the true market value of an asset is made. Political elections and financial markets are aggregations. Aggregation is how the Internet was built: self-directed labor driven by market forces.

When possible, fair aggregations are the most desirable, but it’s non-trivial to define what fair is. Should corporate management be driven by the one-dollar, one-vote system that exists today? Personally, I don’t think so. I think it sucks. I think employees deserve a vote simply because they have an obvious stake in the company. As much as the current, right-wing, state of the American electorate infuriates me, I really like the fact that citizens have the power to fire bad politicians. (They don’t use it enough; incumbent victory rates are so high that a bad politician has more job security than a good programmer.) Working people should have the same power over their management. By accepting a wage that is lower than the value of what they produce, they are paying their bosses. They have a right to dictate how they are managed, and to insist on the mentorship and training that convexity is making essential.

Because it’s so hard to determine a fair aggregation in the general case, there’s always some room for divination and arrogation, or even coercion in extreme cases. For example, our Constitution is a case of (secular, well-informed) divination on the matter of how to build a principled, stable and rational government, but it sets up an aggregation that we use elect political leaders. Additionally, if a political leader were voted out of office but did not hand over power, he’d be pushed out of it by force (coercion). Trust is what enables self-organizing (or, at least, stable) divination. People will grant power to leaders based on abstract principles if they trust those ideas, and they’ll allow representatives to act on their behalf if they trust those people.

Needless to say, convex payoffs to group efforts generate an important role for trust. That’s what the “stone soup” parable is about; because there’s no trust in the community, people hoard their own produce instead of sharing, and no one has had a decent meal for months. When outside travelers offer a nonexistent delicacy– the stone is a social catalyst with no nutritional value– and convince the other villagers to donate their spare produce, they enable them all to work together. So they get a nutritious bowl of soup and, one hopes, they can start to trust each other and build at least a barter or gift economy. They all benefit from the “stone soup”, but they were deceived.

Convex dishonesty isn’t always bad. It is the act of “borrowing” trust by lying to people, with the intent to pay them back out of the synergistic profits. Sometimes convex dishonesty is exactly what a person needs to do in order to get something accomplished. Nor is it always good. Failed convex frauds are damaging to morale, and therefore they often exacerbate the lack-of-trust problem. Moreover, there are many endeavors (e.g. pyramid schemes) that have the flavor of convex fraud but are, in reality, just fraud.

This, in fact, is why modern finance exists. It’s to replace the self-divinations that pre-financial societies required to get convex projects done with a fairer aggregation system that properly measures, and allows the transfer of, risks.

Credibility

For macroscopic considerations like the fair prices of oil or business equity, financial aggregations seem to work. What about the micro-level concern of what each worker should do on a daily basis? That usually exists in the context of a corporation (closed system) with specific authority structures and needs. Companies often attempt to create internal markets (tough culture) for resources and support, with each team’s footprint measured in internal “funny money” given the name of dollars. I’ve seen how those work, and they often become corrupt. The matter of how people direct the use of their time is based on an internal social currency (including job titles, visibility, etc.) that I’ve taken to calling credibility. It’s supposed to create a meritocracy, insofar as the only way one is supposed to be able to get credibility is through hard work and genuine achievement, but it often has some severely anti-meritocratic effects.

So why does your job (probably) Suck? Your job will generally suck if you lack credibility, because it means that you don’t control your own time, have little choice over what you do and how you do it, and that your job security is poor. Your efforts will be allocated, controlled, and evaluated by an external party (a manager) whose superiority in credibility grants him the right of self-divination. He gets to throw your time into his convex project, but not vice versa. You don’t have a say in it. Remember: he’s got credibility, and you lack it.

Credibility always generates a black market. There is no failing in this principle. Performance reviews are gamed, with various trades being made wherein managers offer review points in exchange for non-performance-related favors (such as vocal support for an unrelated project, positive “360-degree reviews”, and various considerations that are just inappropriate and won’t be discussed here) and loyalty. Temporary strongmen/thugs use transient credibility (usually, from managerial favoritism) to intimidate and extort other people into sharing credit for work accomplished, thus enabling the thug to appear like a high performer and get promoted to a real managerial role (permanent credibility). You win on a credibility market by buying and selling it for a profit, creating various perverted social arbitrages. No organization that has allowed credibility to become a major force has avoided this.

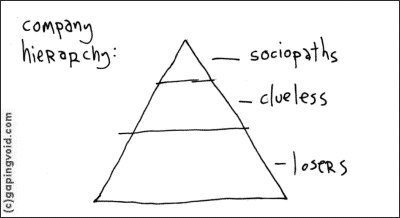

Now I can discuss the hierarchy as immortalized by this cartoon from Hugh MacLeod:

![zzzzazzdggg49.jpg]()

Losers are not undesirable, unpopular, or useless people. In fact, they’re often the opposite. What makes them “losers” is that, in an economic sense, they’re losing insofar as they contribute more to the organization than they get out of it. Why do they do this? They like the monthly income and social stability. Sociopaths (who are not bad people; they’re just gamblers) take the other side of that risk trade. They bear a disproportionate share of the organization’s risk and work the hardest, but they get the most reward. They have the most to lose. A Loser who gets fired will get another job at the same wage; a Sociopath CEO will have to apply for subordinate positions if the company fails. Clueless are a level that forms later on when this risk transfer becomes degenerate– the Sociopaths are no longer putting in more effort or taking more risk than anyone else, but have become an entitled, complacent rent-seeking class– and they need a middle-management layer of over-eager “useful idiots” to create the image (Effort Thermocline) that the top jobs are still demanding.

What’s missing in this analysis? Well, there’s nothing morally wrong, at all, with a financial risk transfer. If I had a resource that had a 50% chance of yielding $10 million, and 50% chance of being worthless, I’d probably sell it to a rich person (whose tolerance of risk is much greater) for $4.9 million to “lock in” that amount. A +5-million-dollar swing in personal wealth is huge to me and minuscule to him. It’d be a good trade for both of us. I’d be paying a (comparably small) $100,000 risk premium to have that volatility out of my financial life. I’m not a Loser in this deal, and he’s not a Sociopath. It’s by-the-book finance, how it’s supposed to work.

What generates the evil, then? Well, it’s the credibility market. I don’t hold the individual firm responsible for prevailing financial scarcity and, thus, the overwhelmingly large number of people willing to make low-expectancy plays. As long as that firms pays its people reasonably, it has clean hands. So the financial Loser trade is not a sign of malfeasance. The credibility market’s different, because the organization has control over it. It creates the damn thing. Thus, I think the character of the risk transfer has several phases, each deserving its own moral stance:

- Financial risk transfer. Entrepreneurs put capital and their reputations at risk to amass the resources necessary to start a project whose returns are (macroscopically, at least) convex. This pool of resources is used to pay bills and wages, therefore allowing workers to get a reliable, recurring monthly wage that is somewhat less than the expected value of their contribution. Again, there’s nothing morally wrong here. Workers are getting a risk-free income (so long as the business continues to exist) while participating in the profits of industrial macro-convexity.

- De-risking, entrenchment, and convex fraud. As the business becomes more established, its people stop viewing it as a risk transfer between entrepreneurs and workers, and start seeing it (after the company’s success is obvious) as a pool of “free” resources to gain control over. Such resources are often economic (“this place has millions of dollars to fund my ideas”) but reputation (“imagine what I could do as a representative of X”) is also a factor. People begin making self-divination (convex fraud) gambits to establish themselves as top performers and vault into the increasingly complacent, rent-seeking, executive tier. This is a red-ocean feeding frenzy for the pile of surplus value that the organization’s success has created.

- Credibility emerges, and becomes the internal currency. Successful convex fraudsters are almost always people who weren’t part of the original founding team. They didn’t get their equity when it was cheap, so now they’re in an unstable positions. They’re high-ranking managers, but haven’t yet entwined themselves with the business or won a significant share of the rewards/equity. Knowing that their success is a direct output of self-divination (that is, arrogation) they use their purloined social standing to create official credibility in the forms of titles (public statements of credibility), closed allocation (credibility as a project-maker and priority-setter), and performance reviews (periodic credibility recalibrations). This turns the unofficial credibility they’ve stolen into an official, secure kind.

- Panic trading, and credibility risk transfer. Newly formed businesses, given their recent memory of existential risk, generally have a cavalier attitude toward firing and a tough culture, which I’ll explain below. This means that a person can be terminated not because of doing anything wrong or being incompetent, but just because of an unlucky break in credibility fluctuations (e.g. a sponsor who changes jobs, a performance-review “vitality curve”). In role-playing games, this is the “killed by the dice” question: should the GM (game coordinator who functions as a neutral party, creating and directing the game world) allow characters, played well, to die– really die, in the “create a new character” sense, not in the “miraculously resurrected by a level-18 healer” sense– because of bad rolls of the dice? In role-playing games, it’s a matter of taste. Some people hate games where they can lose a character by random chance; others like the tension that it creates. At work, though, “killed by the dice” is always bad. Tough-culture credibility markets allow good employees to be killed by the dice. In fact, when stack-ranking and “low performer” witch hunts set in, they encourage it. This creates a lot of panic trading and there’s a new risk transfer in town. It’s not the morally acceptable and socially-positive transfer of financial risk we saw in Stage 1. Rather, it’s the degenerate black-market credibility trading that enables the worst sorts of people (true psychopaths) to rise.

- Collapse into feudalistic rank culture. No one wants a job where she can be fired “for performance” because of bad luck, so tough cultures don’t last very wrong; they turn into rank cultures. People (Losers) panic-trade their credibility, and would rather subordinate to get some credibility (“protection”) from a feudal lord (Sociopath) than risk having none and being flushed out. The people who control the review process become very powerful and, eventually, can manufacture enough of an image of high performance to become official managers. You’re no longer going to be killed by the dice in a rank culture, but you can be killed by a manager because he can unilaterally reduce your credibility to zero.

- Macroscopic underperformance and decline. Full-on rank culture is terribly inefficient, because it generates so much fourth-quadrant work that serves the need of local extortionists (usually, middle managers and their favorites) but does not help the business. Eventually, this leads to underperformance of the business as a whole. Rank culture fosters so much incompetence that trust breaks down within the organization, and it’s often permanent. Firing bad apples is no longer possible, because the process of flushing them away would require firing a substantial fraction of the organization, and that would become so politicized and disruptive as to break the company outright. Such companies regularly lapse into brief episodes of “tough culture”, when new executives (usually, people who buy it as its market value tanks) decide that it’s time to flush out the low performers, but they usually do it in a heavy-handed, McKinsey-esque way that creates a new and equally toxic credibility market. But… like clockwork, those who control said black markets become the new holders of rank and, soon enough, the official bosses. These mid-level rank-holders start out as the mean-spirited witch-hunters (proto-Sociopaths) who implement the “low performer initiative” but they eventually rise and leave a residue of strategically-unaware, soft, complacent and generally harmless mid-ranking “useful idiots” (new Clueless). Clueless are the middle managers who get some power when the company lurches into a new rank culture, but don’t know how to use it and don’t know the main rule of the game of thrones: you win or you die.

- Obsolescence and death. Self-explanatory. Some combination of rank-culture complacency and tough-culture moral decay turn the company into a shell of what it once was. The bad guys have taken out their millions and are driving up house prices in the area and their wives with too much plastic surgery are on zoning committees keeping those prices high; everyone else who worked at the firm is properly fucked. Sell off the pieces that still have value, close the shop.

That cycle, in the industrial era, used to play out over decades. If you joined a company in Stage 1 in 1945, you might start to see the Stage 4 midlife when you retired in 1975. Now, it happens much more quickly: it goes down over years, and sometimes months for fast-changing startups. It’s much more of an immediate threat to personal job security than it has ever been before. Cultural decay used to be a long-term existential risk to companies not taken seriously because calamity was decades away; now, it’s often ongoing and rapid thanks to the “build to flip” mentality.

To tell the truth about it, the MacLeod rank culture wasn’t such a bad fit for the industrial era. Industrial enterprises had a minimal amount of convex work (choosing the business model, setting strategies) that could be delegated to a small, elite, executive nerve-center. Clueless middle managers and rationally-disengaged (Loser) wage earners could implement ideas delivered from the top without too much introspection or insight, and that was fine because individual work was concave. Additionally, that small set of executives could be kept close to the owners of the company (if they weren’t the same set of people).

In the technological era, individual labor is convex and we can no longer afford Cluelessness, or Loserism. The most important work– and within a century or so, all work where there’s demand for humans to do it– requires self-executivity. The hierarchical corporation is a brachiosaur sunning itself on the Yucatan, but that bright point of light isn’t the sun.

Your job is a call option

If companies seem to tolerate, at least passively, the inefficiency of full-blown rank culture, doesn’t that mean that there isn’t a lot of real work for them to do? Well, yes, that’s true. I’ve already discussed the existence of low-yield, boring, Fourth Quadrant busywork that serves little purpose to the business. It’s not without any value, but it doesn’t do much for a person’s career. Why does it exist? First, let’s answer this: where does it come from?

Companies have a jealously-guarded core of real work: essential to the business, great for the careers of those who do it. The winners of the credibility market get the First Quadrant (1Q) of interesting and essential work. They put themselves on the “fun stuff” that is also the core of the business– it’s enjoyable, and it makes a lot of money for the firm and therefore leads to high bonuses. There isn’t a lot of work like this, and it’s coveted, so few people can be in this set. Those are akin to feudal lords, and correspond with MacLeod Sociopaths. Those who wish to join their set, but haven’t amassed enough credibility yet, take on the less enjoyable, but still important Second Quadrant (2Q) of work: unpleasant but essential. Those are the vassals attempting to become lords in the future. That’s often a Clueless strategy because it rarely works, but sometimes it does. Then there is a third monastic category of people who have enough credibility (got into the business early, usually) to sustain themselves but have no wish to rise in the organizational hierarchy. They work on fun, R&D projects that aren’t in the direct line of business (but might be, in the future). They do what’s interesting to them, because they have enough credibility to get away with that and not be fired. They work on the Third Quadrant (3Q): interesting but discretionary. How they fit into the MacLeod pyramid is unclear. I’d say they’re a fortunate sub-caste of Losers in the sense that they rationally disengage from the power politics of the essential work; but they’re Clueless if they’re wrong about their job security and get fired. Finally, who gets the Fourth Quadrant (4Q) of unpleasant and discretionary work? The peasants. The Losers without the job security of permanent credibility are the ones who do that stuff, because they have no other choice.

Where does the Fourth Quadrant work come from? Clueless middle-managers who take undesirable (2Q) or unimportant (3Q) projects, but manage to take all the career upside (turning 2Q into 4Q for their reports) and fun work (turning 3Q into 4Q) for themselves, leaving their reports utterly hosed. This might seem to violate their Cluelessness; it’s more Sociopathic, right? Well, MacLeod “Clueless” doesn’t mean that they don’t know how to fend for themselves. It means they’re non-strategic, or that they rarely know what’s good for the business or what will succeed in the long-term. They suck at “the big picture” but they’re perfectly capable of local operations. Additionally, some Clueless are decent people; others are very clearly not. It is perfectly possible to be MacLeod Clueless and also a sociopath.

Why do the Sociopaths in charge allow the blind Clueless to generate so much garbage make-work? The answer is that such work is evaluative. The point of the years-long “dues paying” period is to figure out who the “team players” are so that, when leadership opportunities or chances for legitimate, important work open up, the Sociopaths know which of the Clueless and Losers to pick. In other words, hiring a Loser subordinate and putting him on unimportant work is a call option on a key hire, later.

Workplace cultures

I mentioned rank and tough cultures above, so let me get into more detail of what those are. In general, an organization is going to evaluate its individuals based on three core traits:

- subordinacy: does this person put the goals of the organization (or, at least, his immediate team and supervisor) above her own?

- dedication: will she do unpleasant work, or large amounts of work, in order to succeed?

- strategy: does she know what is worth working on, and direct her efforts toward important things?

People who lack two or all three of these core traits are generally so dysfunctional that all but the most nonselective employers just flush them out. Those types– such as the strategic, not-dedicated, and insubordinate Passive-Aggressive and the dedicated, insubordinate, and not-strategic Loose Cannon– occasionally pop up for comic relief, but they’re so incompetent that they don’t last long in a company and are never in contention for important roles. I call them, as a group, the Lumpenlosers.

MacLeod Losers tend to be strategic and subordinate, but not dedicated. They know what’s worth working on, but they tend to follow orders because they’re optimizing for comfort, social approval, and job security. They don’t see any value in 90-hour weeks (which would compromise their social polish) or radical pursuit of improvement (which would upset authority). They just want to be liked and adjust well to the cozy, boring, middle-bottom. If you make a MacLeod Loser work Saturdays, though, she’ll quit. She knows that she can get a similar or better job elsewhere.

MacLeod Clueless are subordinate and dedicated but not strategic. They have no clue what’s worth working on. They blindly follow orders, but will also put in above-board effort because of an unconditional work ethic. They frequently end up cleaning up messes made by Sociopaths above and Losers below them. They tend to be where the corporate buck actually stops, because Sociopaths can count on them to be loyal fall guys.

MacLeod Sociopaths are dedicated and strategic but insubordinate. They figure out how the system works and what is worth putting effort into, and they optimize for personal yield. They’re risk-takers who don’t mind taking the chance of getting fired if there’s also a decent likelihood of a promotion. They tend to have “up-or-out” career trajectories, and job hopping isn’t uncommon.

Since there are good Sociopaths out there, I’ve taken to calling the socially positive ones the Technocrats, who tend to be insubordinate with respect to immediate organizational authority, but have higher moral principles rooted in convexity: process improvements, teamwork and cooperation, technical and infrastructural excellence. They’re the “positive-sum” radicals. I’ll get back to them.

Is there a “unicorn” employee who combines all three desired traits– subordinacy, dedication, and strategy? Yes, but it’s strictly conditional upon a particular set of circumstances. In general, it’s not strategic to be subordinate and dedicated. If you’re strategic, you’ll usually either optimize for comfort and be subordinate, but not dedicated, because that’s uncomfortable. If you follow orders, it’s pretty easy to coast in most companies. That’s the Loser strategy. Or, you might optimize for personal yield and work a bit harder, becoming dedicated, but you won’t do it for a manager’s benefit: it’s either your own, or some kind of higher purpose. That’s the Sociopath strategy. The exception is a mentor/protege relationship. Strategic and dedicated people will subordinate if they think that the person in authority knows more than they do, and is looking out for their career interests. They’re subordinating to a mentor conditionally, based on the understanding that they will be in authority, or at least able to do more interesting and important work, in the future.

From this understanding, we can derive four common workplace cultures:

- rank cultures value subordinacy above all. You can coast if you’re in good graces with your manager, and the company ultimately becomes lazy. Rank cultures have the most pronounced MacLeod pyramid: lazy but affable Losers, blind but eager Clueless, and Sociopaths at the top looking for ways to gain from the whole mess.

- tough cultures value dedication, and flush out the less dedicated using informal social pressure and formal performance reviews. It’s no longer acceptable to work a standard workweek; 60 hours is the new 40. Tough culture exists to purge the Loser tier, splitting it between the neo-Clueless sector and the still-Loser rejects, which it will fire if they don’t quit first. So the MacLeod pyramid of a tough culture is more fluid, but every bit as pathological.

- self-executive cultures value strategy. Employees are individually responsible for directing their own efforts into pursuits that are of the most value. This is the open allocation for which Valve and Github are known. Instead of employees having to compete for projects (tough culture) or managerial support (rank culture) it is the opposite. Projects compete for talent on an open market, and managers (if they exist) must operate in the interests of those being managed. There is no MacLeod hierarchy in a self-executive culture.

- guild culture values a balance of the three. Junior employees aren’t treated as terminal subordinates but as proteges who will eventually rise into leadership/mentoring positions. There isn’t a MacLeod pyramid here; to the extent that there may be undesirable structure, it has more to do with inaccurate seniority metrics (e.g. years of experience) than with bad-faith credibility trading.

Rank and guild cultures are both command cultures, insofar as they rely on central planning and global (within the institution) rule-setting. Top management must keep continual awareness of how many people are at each level, and plan out the future accordingly. Tough and self-executive cultures are market cultures, because they require direct engagement with an organic, internal market.

The healthy, “Theory Y” cultures are the guild and self-executive cultures. These confer a basic credibility on all employees, which shuts off the panic trading that generates the MacLeod process. In a guild culture, each employee has credibility for being a student who will grow in the future. In self-executive culture, each employee has power inherent in the right to direct her efforts to the project she considers most worthy. Bosses and projects competing for workers is a Good Thing.

The pathological, “Theory X” cultures are the rank and tough cultures. It goes without saying that most rank cultures try to present themselves as guild cultures– but management has so much power that it need not take any mentorship commitments seriously. Likewise, most tough cultures present themselves as self-executive ones. How do you tell if your company has a genuinely healthy (Theory Y) culture? Basic credibility. If it’s there, it’s the good kind. If it’s not, it’s the bad kind of culture.

Basic credibility

In a healthy company, employees won’t be “killed by the dice”. Sure, random fluctuations in credibility and performance might delay a promotion for a year or two, but the panicked credibility trading of the Theory-X culture isn’t there. People don’t fear their bosses in a Theory-Y culture; they’re self-motivated and fear not doing enough by their own standards– because they actually care. Basic credibility means that every employee is extended enough credibility to direct his own work and career.

That does not mean people are never fired. If someone punches a colleague in the face or steals from the company, you fire him, but it has nothing to do with credibility. You get rid of him because, well, he did something illegal and harmful. What it does mean is that people aren’t terminated for “performance reasons” that really mean either (a) they were just unlucky and couldn’t get enough support to save them in tough-culture “stack ranking”, or (b) their manager disliked them for some reason (no-fault lack-of-fit, or manager-fault lack-of-fit). It does mean that people are permitted to move around in the company, and that the firm might tolerate a real underperformer for a couple of years. Guess what? In a convex world, underperformance almost doesn’t matter.

With convexity, the difference between excellence and mediocrity matters much more than that between mediocrity and underperformance. In a concave world, yes, you must fire underperformers because the margin you get on good employees is so low that one slacker can cancel out 4 or 5 good people. In a convex world, the danger isn’t that you have a few underperformers. You will have, at the least, good-faith low-performers, just because the nature of convexity is to create risk and inequality of return and some peoples’ projects won’t pan out. Thjat’s fine. Instead, the danger is that you don’t have any excellent (“10x”) employees.

There’s a managerial myth that cracking down on “low performers” is useful because they demotivate the “10x-ers”. Yes and no. Incompetent management and having to work around bad code are devastating and will chase out your top performers. If 10xer’s have to work with incompetents and have no opportunity to improve them, they get frustrated and quit. There are toxic incompetents (dividers) who make others unproductive and damage morale, and then there are low-impact employees who just need more time (subtracters). Subtracters cost more in salary than they deliver, but they aren’t hurting anyone and they will usually improve. Fire dividers immediately. Give subtracters a few years (yes, I said years) to find a fit. Sometimes, you’ll hire someone good and still have that person end up as a subtracter at first. That common in the face of convexity– and remember that convexity is the defining problem of the 21st-century business world. The right thing to do is to let her keep looking for a fit until she finds one. Almost never will it take years if your company runs properly.